Blog personnel - News - Religion - Scientology - Droits de l'Homme - Interviews - Livres - etc.

Le blog

Eric Roux

Ministre du culte de L'Eglise de Scientology, après 30 années passées dans le clergé de l'Eglise, Eric Roux est aujourd'hui le président de l'Union des Eglises de Scientology de France et Vice Président du Bureau Européen de L'Eglise de Scientology pour les affaires publiques et les droits de l'homme. Il est aussi Président élu du Conseil International de URI (United Religions Initiative) et le Président du European Interreligious Forum for Religious Freedom.

Ce blog est une initiative personnelle destinée aux gens qui s'intéressent à la spiritualité, ou à ceux qui souhaitent en apprendre plus sur la scientology, à ceux qui pensent que la liberté de conscience est un droit fondamental qui mérite d'être défendu, à mes coreligionnaires ou encore à ceux qui sont curieux...

Ce blog est une initiative personnelle destinée aux gens qui s'intéressent à la spiritualité, ou à ceux qui souhaitent en apprendre plus sur la scientology, à ceux qui pensent que la liberté de conscience est un droit fondamental qui mérite d'être défendu, à mes coreligionnaires ou encore à ceux qui sont curieux...

Galerie (cliquez dessus pour plus d'images)

Rubriques

Dernières notes

Archives

Sites de Scientologie

Association paraînées par l'Eglise de Scientologie

Liberté de Conscience

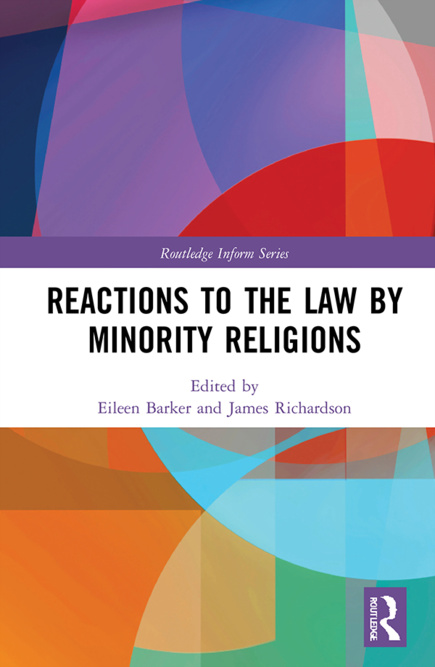

Le livre Reactions to the Law by Minority Religions (réactions à la loi par les religions minoritaires) vient d'être publié chez Routledge (publications académiques depuis 1851). Il contient un chapitre écrit par votre serviteur : "Scientology Behind the Scene, the Law Changer".

Eileen Barker, qui dirigeait l'ouvrage avec James T. Richardson introduit le chapitre comme suit :

2 ombres au tableau cependant : le livre est très cher (mais il existe la version e-book, beaucoup moins chère), et pour ceux qui ne parlent pas anglais, il n'existe pas en français. Quoi qu'il en soit, pour ceux qui veulent tout lire (tous les chapitres sont intéressants et écrits par d'excellents auteurs spécialiste du phénomène religieux), vous pouvez vous le procurer ici.

Pour les anglophones, voici le chapitre en question :

Eileen Barker, qui dirigeait l'ouvrage avec James T. Richardson introduit le chapitre comme suit :

Le chapitre d’Eric Roux sur l’Église de Scientology détaille les batailles juridiques du mouvement pour être reconnu comme une véritable religion. Ses succès dans ce domaine ont sans aucun doute élargi la définition de la religion dans le langage juridique d'une grande partie du monde, permettant ainsi non seulement à la Scientology, mais aussi à d'autres religions d'échapper aux sanctions relatives au fait de ne pas être enregistrées et / ou de bénéficier des avantages de la reconnaissance en tant que religion authentique.

2 ombres au tableau cependant : le livre est très cher (mais il existe la version e-book, beaucoup moins chère), et pour ceux qui ne parlent pas anglais, il n'existe pas en français. Quoi qu'il en soit, pour ceux qui veulent tout lire (tous les chapitres sont intéressants et écrits par d'excellents auteurs spécialiste du phénomène religieux), vous pouvez vous le procurer ici.

Pour les anglophones, voici le chapitre en question :

Scientology behind the scenes

The law changer

Eric Roux

Introduction

In almost 70 years of existence, the Church of Scientology has been confronted by the law probably more than any other religious movement in modern times. It has developed an extraordinary record of interaction with legislation, whether in courts or through its interaction with governments and government agencies. These interactions have sometimes created significant changes in the law regarding freedom of religion, religious recognition and related topics. In many countries, this has been achieved through case law, with the Church of Scientology’s efforts contributing to the development of new definitions of religion that fit with contemporary religious diversity, but also through advocacy before national and supranational governmental organizations. Herein, I will give several examples of how the Church of Scientology reacted to the law through court cases in order to force changes. I also will describe a successful advocacy crusade of the Church within the Council of Europe that resulted in dramatically changed legislation at supranational level.

The Italian case

Italy is emblematic for several reasons. First, the major issue involved a criminal case, and the accusations in it are similar to those repeated in various criminal cases that Scientology has had to face in Europe. It is also emblematic because it occurred in a country which is known for the predominance of the Catholic Church to an extent rarely seen elsewhere.

The case started in 1986, when the carabinieri (Italian police) organized a huge series of simultaneous raids against churches of Scientology in Italy, and placed under arrest 75 ‘leaders’ of the Church under various criminal charges (extortion, fraud, running a criminal conspiracy, abuse of weak people) that eventually were revealed to be false. In 1991, most of the ‘leaders’ were acquitted in a first instance trial. The prosecutor appealed the decision, and on 5 November 1993, the Court of Appeal of Milan rendered a very harsh decision against the Scientologists. That decision was appealed before the Court of Cassation, and in 1995, the Court of Cassation squashed the Court of Appeal decision and sent the case back to that Court. The Court of Appeal persisted in its initial decision in 1996 by once again strongly condemning the Scientologists as criminals. The case went back to the Court of Cassation, which, in October 1997, issued a landmark decision recognizing the religious bona fides of Scientology.

The court, in reaching that conclusion, acknowledged the earlier recognition of the Church as a religion in the United States: “…since the Church of Scientology has been recognized in the U.S. as a religious denomination, it should have been recognized in Italy and thus allowed to practice its worship and to conduct proselytising activities…” (Bandera and others v. Italy 1997).

It also took into account the work of the scholars who had given their opinion on the case: Scholars of religion, the Court noted, acknowledge that Scientology is a religion whose aim is “the liberation of the human spirit through the knowledge of the divine spirit residing within each human being” (Bandera and others v. Italy 1997).

Interestingly, the Italian Court of Cassation, in its decision, entered strong comparisons to other religious practices and concluded that “the circumstance that the religion has brought into being lucrative activities does not distinguish it from other religions nor in itself deprive it of its intrinsic religiosity”. It also concluded that:

Because any religion (…) carries out the catechesis of neophytes and catechumens in special courses, imposes practices, places prohibitions, marks and teaches ways and paths of improvement and ascesis, often very difficult and afflictive, towards and in search of God, so that the books to be read, the courses to be followed, the practices to be performed and the ways of improvement imposed by the [Church of Scientology’s] association in question cannot be defined as illicit based [on such grounds].

(Bandera and others v. Italy 1997)

In its final decision recognizing the religious nature of Scientology, the Court noted that the procedure adopted by the Court of Appeal (which relied on what they thought was the ‘common consideration’ for rejection of the religious nature of Scientology) was wrong. It decided that the criteria that should be taken into account for religious recognition were, in addition to the opinion of religious scholars and the fact that it was recognized in the United States, “the conviction of thousands of members of the association with regard to its religiosity, a fact certainly not irrelevant in order to form the common consideration in this regard” (Bandera and others v. Italy 1997).

This was the first time in Italy that a Supreme Court decision opened the door to recognition of religions, which were not ‘traditional’ in the country, by setting objective criteria based on a pragmatic, positive, open and modern approach to freedom of religion or belief. The Court sent the case back to the Court of Appeal of Milan, which acceded to the Superior Court’s jurisdiction and recognized the religious nature of Scientology on 5 October 2000.

Italy also recognized the religious nature of Scientology in numerous tax case determinations. For example, in 1991, the Criminal Court of Milan recognized that the Church of Scientology could not be subject to commercial taxes due to the religious and not-for-profit nature of its activities. Earlier, the first tax jurisdiction to render a positive decision on Scientology was the Tax Commission of Monza on 27 March 1990:

The Commission considers that the religious nature of Scientology is an established fact, which applies equally to the theory of its teachings, to the salvific contents of the latter such as the religious rites practiced, and to the ecclesiastical character of the way the organization carries out its activities.

(Tax Commission of Monza 1990)

More recently, since 2000, 37 decisions related to tax issues in Italy have recognized the religious nature of Scientology, including three by the Court of Cassation.

Welcome to Australia and beyond

The Australian High Court’s decision regarding the Scientology religion in Church of the New Faith v. Commissioner of Payroll Tax (1983) is a landmark judgment which established the standard definition of religion and religious charities in Australia and New Zealand and, in fact, throughout the Commonwealth of Nations.

The Church of Scientology in the State of Victoria had been asked to pay a tax on salaries, while other religions were exempted of such tax. The Church went through all levels of jurisdiction, including the Supreme Court of Victoria, before finally appealing to the High Court of Australia, the equivalent of the Supreme Court in the United States.

The High Court determined the following: “The Church of Scientology has easily discharged the onus of showing that it is religious. The conclusion that it is a religious institution entitled to tax exemption is irresistible” (Church of the New Faith v. Commissioner of Payroll Tax 1983: 40). It adopted the following definition of religion:

First, belief in a supernatural Being, Thing or Principle; and second, the acceptance of canons of conduct in order to give effect to that belief, though canons of conduct which offend against the ordinary laws are outside the area of any immunity, privilege or right conferred on the grounds of religion. Those criteria may vary in their comparative importance, and there may be a different intensity of belief or of acceptance of canons of conduct among religions or among the adherents to a religion. The tenets of a religion may give primacy to one particular belief or to one particular canon of conduct. Variations in emphasis may distinguish one religion from other religions, but they are irrelevant to the determination of an individual’s or a group’s freedom to profess and exercise the religion of his, or their, choice.

(Church of the New Faith v. Commissioner of Payroll Tax 1983: 10)

This 60-page decision opened the door for other minority religions in Australia to be recognized, including indigenous religions hitherto denied by the churches of the colonizers, and for them also to benefit from tax exemption. This decision has been cited in a series of decisions in other nations of the Commonwealth. For example, the New Zealand Inland Revenue, in its June 2001 report of the Policy Advice Division on Tax and Charities: A Government Discussion Document on Taxation Issues Relating to Charities and Non-Profit Bodies, stated:

With respect to the advancement of religion, there is no distinction in case law between one religion and another or one sect and another, so the advancement of any religious doctrine could be considered charitable…. For purposes of the law, the criteria of religion are the belief in a supernatural being, thing or principle and the acceptance of certain canons of conduct in order to give effect to that belief.

(2001: Chapter 3.15: 18)

Similarly, in February 2005, the English Lords of Appeal in Secretary of State for Education and Employment and others (Respondents) ex parte Williamson (Appellant) and others relied on the Australian Scientology decision as an ‘illuminating’ case for the definition of religion, in a case not related to Scientology:

Courts in different jurisdictions have on several occasions had to attempt the task [of reaching a definition of religion], often in the context of exemptions or reliefs from rates and taxes, and have almost always remarked on its difficulty. Two illuminating cases are the decisions of Dillon J in In re South Place Ethical Society [1980] 1 WLR 1565 and that of the High Court of Australia in Church of the New Faith v. Commissioner of Pay-Roll Tax (Victoria) (1983) 154 CLR 120, both of which contain valuable reviews of earlier authority. The trend of authority (unsurprisingly in an age of increasingly multi-cultural societies and increasing respect for human rights) is towards a ‘newer, more expansive, reading’ of religion. (2005)

The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom

The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom also recognized the conclusions of the Australian High Court to decide on Scientology. On 11 December 2013, the UK Supreme Court rendered a decision regarding the case of a couple who had been denied the right to marry in their Church by the Registrar General. The Registrar General, who is responsible for the civil registration of births, adoptions, marriages, civil partnerships and deaths in England and Wales, based his refusal on a precedent by a Court of Appeal: the ‘Segerdal’ decision which had stated in 1970 that the Church of Scientology was not a ‘place of meeting for religious worship’ within the meaning of the Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 (R v. Registrar General 1970). Thus, the only way for the Scientology couple to have the decision overturned was to challenge it before the Supreme Court. The decision that followed has been recognized as a milestone for minority religions.

In a manner which might well resonate for some time, Lord Toulson [the leading judge], in Hodkin [2013: 19, name of the decision], has taken the debate about the nature of religion into new territory. Lord Toulson recalibrated the vocabulary, from the idea of definitions or the search for essentials, to the more open quest for a description of religion.

(Cranmer et al. 2016: 27)

To reach his conclusion (which was unanimously agreed by the whole Court), the leading Judge in the Supreme Court stated that “from the considerable volume of common law jurisprudence, [he] would select two cases for particular attention” – one of the two being the above-mentioned judgment of the High Court of Australia cited above. He also reviewed the ‘Segerdal’ decision and in that regard judged:

60. On the approach which I have taken to the meaning of religion, the evidence is amply sufficient to show that Scientology is within it; but there remains the question whether the chapel at 146 Victoria Street is “a place of meeting for religious worship”.

61. In my view the meaning given to worship in Segerdal was unduly narrow, but even if it was not unduly narrow in 1970, it is unduly narrow now.

(R v. Registrar 2013: 19)

Then, with regards to the definition of religious worship:

62. I interpret the expression ‘religious worship’ as wide enough to include religious services, whether or not the form of service falls within the narrower definition adopted in Segerdal. This broader interpretation accords with standard dictionary definitions. The Chambers Dictionary, 12th ed (2011) defines the noun ‘worship’ as including both ‘adoration paid to a deity’, etc., and ‘religious service’, and it defines ‘worship’ as an intransitive verb as “to perform acts of adoration; to take part in religious service”. Similarly, the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 12th ed (2011), defines ‘worship’ as including both “the feeling or expression of reverence and adoration of a deity” and “religious rites and ceremonies”.

63. The broader interpretation accords with the purpose of the statute in permitting members of a religious congregation, who have a meeting place where they perform their religious rites, to carry out religious ceremonies of marriage there. Their authorisation to do so should not depend on fine theological or liturgical niceties as to how precisely they see and express their relationship with the infinite (referred to by Scientologists as ‘God’ in their creed and universal prayer). Those matters, which have been gone into in close detail in the evidence in this case, are more fitting for theologians than for the Registrar General or the courts.

64. There is a further significant point. If, as I have held, Scientology comes within the meaning of a religion, but its chapel cannot be registered under PWRA because its services do not involve the kind of veneration which the Court of Appeal in Segerdal considered essential, the result would be to prevent Scientologists from being married anywhere in a form which involved use of their marriage service. They could have a service in their chapel, but it would not be a legal marriage, and they could have a civil marriage on other ‘approved premises’ under section 26(1)(bb) of the Marriage Act, but they could not incorporate any form of religious service because of the prohibition in section 46B(4). They would therefore be under a double disability, not shared by atheists, agnostics or most religious groups. This would be illogical, discriminatory and unjust. When Parliament prohibited the use of any ‘religious service’ on approved premises in section 46B(4), it can only have been on the assumption that any religious service of marriage could lawfully be held at a meeting place for religious services by registration under PWRA.

(R v. Registrar 2013: 19)

Thus, the Court unanimously overruled the ‘Segerdal’ decision and ordered the Registrar to register the Chapel of the Church of Scientology of London as a place of worship. This decision has completely redefined the scope of what is a religion and means that minority religions should not be discriminated against in the United Kingdom (Figure 4.1).

The United States Internal Revenue Service decision

After years of battle against the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) in the United States, Scientology won in 1993 what they called ‘the war’. It was celebrated by Scientologists all over the world with these words: “The war is over!” The IRS had finally ruled that Scientology was a genuine religion and so became tax exempt in the United States. After years of conflict between the IRS and the Church of Scientology on the topic of tax exemption for religious organizations, and after discussion with the ecclesiastical leader of the Church of Scientology, Mr David Miscavige, the IRS carried out the most thorough investigation it had ever done for any applicant claiming eligibility for religious tax exemption. This included a full and extensive review of all operations and financial records and a complete review of all aspects of the policies of the Church as well as its practices at national and international levels. By the end of its investigation, IRS had inspected more than 1 million pages of data regarding the Church of Scientology.

To render its tax-exemption rulings, the IRS had to decide that Scientology is a genuine religion; that the Churches of Scientology and their related charitable and educational institutions are operated exclusively for religious purposes; that the Churches of Scientology and their charitable and educational institutions operate for the benefit of the public interest and not for the interests of private individuals and that no part of the net earnings of these Churches of Scientology and their charitable and educational institutions are used for the financial benefit of any individual or non charitable entity. For this determination, the IRS employs a ‘facts and circumstances’ test, looking at the following criteria:

• A distinct legal existence;

• A recognized creed and form of worship;

• A definite and distinct ecclesiastical government;

• A formal code of doctrine and discipline;

• A distinct religious history;

• A membership not associated with any other Church or denomination;

• An organization of ordained ministers;

• Ordained ministers selected after completing prescribed studies;

• A literature of its own;

• An established place (or places) of worship;

• Regular congregations;

• Regular religious services;

• Sunday schools for religious instruction of the young; and

• Schools for the preparation of its ministers.

All materials related to this ruling, more than 14 linear feet of documents, are available for inspection by the members of the public at the IRS National office.

Surprisingly in France

The strong opposition of some French government agencies against Scientology (and the strong discrimination Scientologists have faced in that country) has led many to state that France did not consider Scientology to be a religion. However, many French courts have recognized the religious nature of the Church since the 1980s. As Professor Marco Ventura stated:

French case law always confined itself to findings by the Paris Court of Appeal which had, back in 1980 already stated that “Scientology activities seem to correspond to activities normally pertaining to the definition usually given to a religion, since the Court observes that in Scientology, despite a lack of metaphysical concern normally attached to the great traditional Western religions, the subjective element of faith comes with an objective factor which is the existence of a human community, however small, the members of which are bound with a system of beliefs and of practices relating to sacred things”. In the subsequent cases, regardless of the conclusions that were reached, French Courts never denied the religious nature of the Church of Scientology.

(Ventura 2015: 19)

In 1981, two decisions by the Court of First Instance of Paris reached the same conclusion (Valentin v. Prosecution 1981; Laarhuis v. Prosecution 1981). In 1987, in a divorce case, the Dijon’s Court of Appeal ruled that the fact that one of the members of a divorcing couple had abandoned Catholicism for Scientology was protected by the right to freedom of religion and should not affect negatively the opinion of the Court (1987).

In an emblematic case, Church of Scientology of Paris v. Interpol, the Court of First Instance of Nanterre ruled in 1994 that “Its [Scientology’s] object is thus a religious discipline, insofar as its members are united by a system of beliefs and practices relating to sacred things. Moreover, this religious character has been recognized in various judicial decisions in various countries” (Scientology v. Interpol 1994:18). Then, in 1996, the Administrative Court of Paris had been asked by the Church to cancel a ruling by the City of Clichy-la-Garenne which had forbidden the distribution of religious literature by Scientology. In his decision, the judge ruled that this ruling by the City of Clichy-la-Garenne was a violation of the right to freedom of religion of the Scientologists and their Church and cancelled it (Church of Scientology v. Clichy-la -Garenne 1996). On 28 July 1997, the Court of Appeal of Lyon stated that:

To the extent that a religion can be defined by the coincidence of two elements, an objective element, the existence of even a small community, and a subjective element, a common faith, the Church of Scientology can claim the title of religion and freely develop, within the framework of the existing laws, its activities including its missionary activities, even of proselytizing.

(Veau et al. v. the General Prosecutor 1997: 21)

This decision triggered some controversy as the then Minister of Interior complained that courts had no power to decide what is a religion and what is not. This political controversy led the Prosecutor’s Office to appeal the decision before the Court of Cassation. The Court of Cassation ruled that, indeed, this part of the judgment was ‘superabundant’, in the sense of not necessary, but upheld the judgment of the Court of Appeal (General Prosecutor v. Scientology 1999).

The Belgian victory

On 11 March 2016, in a landmark decision, the Criminal Court of Brussels found in favour of the defendants and completely dismissed all charges against the Church of Scientology of Belgium, the Church of Scientology International European Office for Public Affairs and Human Rights and 11 Scientologists who were current or former staff members (Scientology v. Federal Prosecutor 2016: 122). This 173-page judgment was issued after a two-month criminal trial that ended in December 2015, following an 18-year investigation. It unequivocally rejected all charges and acquitted all defendants.

The two Church entities and the 11 Scientologists had been subjected for 18 years to numerous charges including fraud, extortion, running a criminal enterprise, violating privacy and the illegal practice of medicine. The prosecution had called for the Church entities to be disbanded, along with prison terms for the defendant members.

For almost two decades, the media, the prosecutor in charge of the case and even the State Security (Belgian intelligence services) had accused the Church of being a ‘cult’ and had based all their accusation mainly on this non-legally defined concept. The Court found that the charges brought against the defendants were ‘deficient’, ‘incoherent’, ‘contradictory’, ‘inconsistent’, ‘vague’, ‘imprecise’, ‘unclear’ and ‘incomplete’. The Court also determined the criminal investigation and accusations violated the defendants’ right to their presumption of innocence because the prosecutor had placed their religion on trial inappropriately by presuming that the defendants were guilty solely because they were members of the Church of Scientology:

In other words, before it is the trial of each of the defendants prosecuted before this Court, it is primarily the trial of Scientology, in its ideological meaning, that the Prosecution intended to try. (…) “Like a Catholic priest accused of paedophilia or fraud to charities, or a terrorist responsible of terrorist attacks, whose criminal behaviours would not be judged according to the teachings of the Bible or the Koran or some of their excerpts, although sometimes very explicit, the acts of the defendants cannot be considered criminal on the sole basis of the ideological or doctrinal writings of their faith, putting the burden on them to prove to the contrary.”

(Scientology v. Federal Prosecutor 2016: 150)

The background to this trial involved a 670-page Belgium Parliamentary Commission Report that stigmatized 189 religious organizations, including Baha’is, Buddhists, Scientologists, Seventh-day Adventists, Mormons, Amish and Pentecostals, all of which were labelled as ‘dangerous cults’ without any investigation, cross examination or right to reply by the religions themselves. This report was used as ‘evidence’ by the prosecution, and the Church of Scientology challenged these assertions before the court as illegal. The Court stated that:

The Court shares the views of the defence…: it seems obvious that by presenting in particular a list of 189 movements it considered harmful, the Parliamentary Commission made a value judgment which it was not entitled to do, violating the presumption of innocence which must benefit everyone. (…) According to the Court, it is at the level of the conclusions drawn from its works that the Commission exceeded its powers and eventually violated certain fundamental rights guaranteed in particular under the European Convention on Human Rights, including the presumption of innocence which was just censured.

(2016: 122)

The Spanish battle

Scientology and Scientologists in Spain have endured many difficulties before reaching the position they occupy today. In 1988, the Guardia Civile raided a symposium of the International Association of Scientologists and arrested 72 members, including the President of the Church of Scientology International, Mr Heber Jentzsch. The investigatory judge, Jose-Maria Vasquez Honrubia, started from the premise that Scientology should be banned and he stated that he feared Scientologists could hypnotize him during his investigations. He even accused the Church of Scientology of being behind the death of the dictator Franco, based on secret service reports that a Scientology boat was not far from the place where sickness killed him (in fact, Franco died in his bed in Madrid while the boat in question was on the Mediterranean coast). Thirteen years later, in 2001, all Scientologists without exception were acquitted in a final decision of the Spanish Criminal Court. On 7 December 2001, the Spanish newspaper El Pais wrote:

The acquittal by the Provincial Court of Madrid of members of the Church of Scientology, after 17 years of persecution by the judiciary, to which is added the intolerable slowness of our judicial system, highlights the improper use of a criminal device to oppose models of moral and religious conduct that are dissimilar to contemporary trends, or that, by their novelty or because they deviate from the most fashionable practices, raise suspicion for being abnormal phenomena. If we add to this misuse of criminal law, as was the case in this trial, the accusation of a prosecutor unable to provide evidence and an instruction without the guarantees that constitute our rule of law, it must result in an acquittal, even if it is somewhat late.

(Perseguidos Absueltos 2001)

But in ensuing years, Scientology still had to fight to be recognized as a religion at the National level. When its registration was rejected by the Ministry of Justice, which in Spain operates the registry of religious entities, Scientology challenged the rejection in court. Finally, on 31 October 2007, the National Court in Madrid (Audiencia Nacional) issued a unanimous decision affirming the right to religious freedom in Spain by recognizing that the National Church of Scientology of Spain is a religious organization entitled to the full panoply of religious rights that flow from entry in the government’s Registry of Religious Entities. In its Ruling, the Audiencia Nacional stated:

The positive conclusion favourable to its consideration as a religious entity emerges ‘prima facie’ from its bylaws as well as from the doctrine/teachings presented, and also from the fact that the association is similar to others that are rightfully registered in official registries in countries of similar jurisprudence and culture.

(Scientology v. Ministry of Justice 2007)

Based on these findings, the Court “declare[d] the right of the [National Church of Scientology of Spain] to its registration in the Registry of Religious Entities of the Ministry of Justice” (2007). This decision was the first of its kind in Spain and opened the door to other ‘non-traditional’ religions and religious minorities being included in the Register of Religious Entities of Spain.

The Germans

Germany has had a long history of discrimination by the executive branch against Scientologists since the 1990s. Nevertheless, its Courts have a long history of recognizing Scientology as a religious organization entitled to the protection of freedom of religion or belief guaranteed by the German Constitution, its fundamental law.

In 1985, the Court of Stuttgart rendered a decision about the case of a member of the Church of Scientology who had been distributing religious literature in the street. He had been fined and forbidden to continue by the local police on the grounds that he did not have authorization for commercial activity. The Court found that the defendant was not only exercising his right to freedom of speech and freedom of religion but also that his activity could not be characterized as commercial, as it was religious:

The Court has no evidence that would suggest that the books, pamphlets and other materials for study and information offered for sale would not serve these religious purposes; the same applies to courses, seminars and auditing subject to financial contribution, and all of them - according to the description of the person concerned and of his Church - directly constitute religious activities and practices, serve equally directly religious purposes, and are underpinned by religious motives. The Court has no doubt as to the characterization of this purpose;

(...)

Whereas the interested person acted in the service of a goal directly religious (...) [he] must be acquitted.

(Court of Stuttgart 1985)

In 1988, the Superior Court of Hamburg decided that the Church of Scientology of Hamburg had to be recognized as a Church in the meaning of the Constitution:

The association seeking registration must be recognized as a Church within the meaning of Article 140 of the Basic Law (Constitution) and Article 137 WRV (Constitution of the Weimar Republic).

The characteristics required for a group to be recognized as a religion under the above-mentioned law are, however, uncertain. Nevertheless, the criteria that can be demanded of a Church are undoubtedly present in the present case. We are dealing with an association that is not only united for ideological purposes but also pursues a transcendental goal. This is evident not only in view of its statutes, but also its ecclesiastical rules, all elements included in the application for registration.

(Court of Hamburg 1988)

In 1989, the Regional court of Frankfurt decided a case brought by a former member of the Church of Scientology who wanted to be reimbursed for money paid to receive auditing (a spiritual and religious practice of Scientology). She based her case on the fact that auditing was a psychological therapy violating the law on healers and the law on advertising medicine. The court found that auditing was part of the religious practice of Scientology, that it could not be confused with any medical or psychological practice and that the plaintiff had known this from the beginning:

Auditing does not intervene in the field of medical therapeutics. It has its origins in the defendant’s religious vision, which is protected by the Fundamental Law, and is the core of spiritual / religious practice and the manner in which Scientology ministers can contribute to the salvation of their members. Like most religious and philosophical communities, the Respondent herself describes Scientology as an approach to mankind, understood in its unity, unity of body and soul.

(Regional Court of Frankfurt 1989)

A similar decision had already been rendered in 1976 by the Court of First Instance of Stuttgart.

In November 1997, the Federal Administrative Court of Germany issued a landmark judgment, stating that Scientology services were of a spiritual nature and not for commercial purposes. This decision followed an attempt by Baden-Württemberg to cancel the registration of a Scientology mission on the grounds that it violated the state’s statutes and engaged in non-religious business activities.

The Federal Administrative Court denied in 1997 the arguments used by the Administrative Courts to reject the religious nature of the Church of Scientology, finding the religious nature of the organization to be compatible with the payment of the spiritual services that were offered. The Federal Court also recognized that one “has to rely especially on the fact that the ideas of the Church of Scientology (especially the auditing) that are manifested in the framework of services in kind, and the association’s services are only proposed by its religious organization and subdivisions and that its religious reference is recognized by its members”. This clarification later allowed Courts like the Higher Court of Hamburg in 1998, the Administrative Court of Stuttgart in 1999 and the Court of Social Affairs of Nuremberg in 2000 to ascertain the religious nature of the Church of Scientology.

(Ventura 2015: 7)

Thus, there are dozens of decisions in Germany recognizing the religious nature of Scientology, which makes Scientology unique in regard to case law on religious issues in Germany.

Other decisions of note

There are many other countries with case law related to freedom of religion and belief or religious recognitions involving Scientology. The European Court of Human Rights has three times ruled in favour of the Church of Scientology against the Russian Federation for the latter’s refusal to register the Church of Scientology on its religious entities register (Kimlya and Others v. Russia 2009; Church of Scientology of Moscow v. Russia 2007; Church of Scientology of St Petersburg and Others v. Russia 2014). These decisions have frequently been cited in subsequent decisions of the Court with respect to Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, protecting freedom of religion or belief.

A decision that created an important precedent was taken in 1979 by the European Commission of Human Rights (the predecessor of the European Court of Human Rights) recognizing the collective and community dimension of the Church of Scientology’s subjectivity. According to the Commission, by filing a petition pursuant to the European Convention of Human Rights, the Church of Scientology in its dimension as an “ecclesiastical body” acted “actually in the name of the believers” and “the consequence must be that such a body is capable of owning and exerting, personally, as a representative of believers, the rights which are provided in Article 9” (X and Church of Scientology v. Sweden 1979: 70). This was the first time that the Commission recognized freedom of religion as a collective right that could be defended by a Church, as such.

In the Netherlands, the Court of Amsterdam recognized Scientology: “due to the goal pursued, auditing and training were not different from the religious activities of other ecclesiastical institutions” (Church of Scientology of Amsterdam v. the Inspector of the Tax Services 2013).

In Austria, on 1 August 1995, the Independent Administrative Court of Vienna, Austria, stated that:

In addition to the fact that after several decades of thorough investigations, Scientology has been granted the status of a bona fide religion and charitable organization by the IRS, less than two years ago in the United States, the country with the greatest number of Churches of Scientology, sufficient evidence was also given by [the Church] to convince us that the Church of Scientology of Austria is a religion.

(1995: 27)

The battle within the Council of Europe

After describing various court cases where the Church of Scientology has brought innovation and precedents in international case law, I will now describe some efforts of the Church as a law changer through advocacy before national or supranational governmental organizations.

On four different occasions between 1990 and 2011, attempts were made to bring about restrictions on religious minorities (derogatorily named ‘sects’ or ‘cults’) through the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). On each occasion, the Church of Scientology was present and instrumental in working with NGOs, parliamentarians and other concerned people in order to counter the discriminatory proposals put before the Assembly and the Committee of Ministers (the highest authoritative body of the Council of Europe). International ‘Observatories on Sects’ was a common theme in these proposals (a proposal that would have targeted and placed under special observation ‘sects’ with the intention of isolating them and classifying them as groups with no religious protection). Each time, the discriminatory measures were diluted or not accepted. What may be the last of these efforts is described here.

On 7 September 2011, Rudy Salles, who was at that time a member of the National Assembly in France and part of the French delegation to PACE, was appointed as the Assembly’s Rapporteur for a Report on the “protection of minors against sectarian influence”. French ‘anti-cult’ movements had been seeking to create a ‘European Observatory on sectarian movements’ for many years without success. European governments have broadly held the position that common criminal law can take care of the few cases involving so-called ‘sects’ and that investing energy and money for creating special observatories for such a non-problem would be wasteful and discriminatory. Nevertheless, on 3 March 2014, the report drafted by Rudy Salles put forth such a measure (amongst other discriminatory proposals) on the PACE agenda for voting on 10 April during the plenary session. The draft report proposed a resolution and a recommendation, both of which were effectively attempting to export the French anti-sect model and policies to the European level and the 47 countries of the Council of Europe, including the creation of a European Observatory of Sects at the level of the Council of Europe. The report also contained a proposal to provide resources to so-called traditional religions in order to have them support the effort:

When it comes to preventing and combating excesses of sects, some Council of Europe member states grant significant leeway to civil society and the ‘traditional’ Churches (Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant). In this case, it is necessary to provide these stakeholders with sufficient resources for effectively performing their tasks in terms of advising and assisting the victims of such excesses and their relatives.

(Salles 2014)

Realizing what it could mean for the rights of minority religions across Europe if such recommendations were implemented, I alerted many other movements of the risks stemming from this initiative. While none were aware of this French initiative, they immediately realized how this draft resolution was contrary to international standards on freedom of religion or belief. This led to a coalition of religious movements and NGOs from all over the world. More than 80 NGOs, faith-based or not, wrote to the President of PACE to protest against the draft report and the proposed resolution.

As stated in the Council of Europe Human Rights blog:

Readers will remember that Israeli President Simon Peres, Turkey’s Deputy Prime Minister and many others were outraged by an assembly resolution last year which they thought threatened the ancient practice of male circumcision. The assembly deftly rebuffed the criticism and faint whispers of anti-Semitism, claiming it only wished to start a dialogue.

Now, in a capital letter-headlined article published by World Religion News, the assembly has been warned that the new debate it has opened on ‘sect observatories’ has stoked the ire of yet more religious groups.

(Anon 2014)

Campaigning with the Church of Scientology were NGOs from the Evangelicals, Muslims, Sikhs, Catholics, Hindus, but also many humanist or non-affiliated NGOs, such as the Moscow Helsinki Group, at that time headed by its co-founder Lyudmila Alexeyeva, considered a hero in the fight for freedom in the Soviet Union, who personally wrote to the President of PACE to alert her to the danger of such legislation. Protesters also included well-known figures as Dr Aaron Rhodes, former Executive Director of the International Helsinki Committee and Co-Founder of the Freedom Rights Project, and Vincent Berger, former Jurisconsult of the European Court of Human Rights and Law Professor at the College of Europe.

The campaign included meeting with dozens of members of the various national delegations of the Council of Europe, making sure that they understood what legislation such as that drafted by Rudy Salles meant in terms of human rights. It also included organizing side events on the premises of the Parliamentary Assembly in Strasbourg which dozens of members of PACE attended.

Finally, on 10 April 2014, PACE decided to uphold its standards in terms of freedom of religion or belief and voted down the recommendations proposed by Salles and transformed his proposal into a resolution protecting the rights of religious minorities, reversing completely what had been written in the draft. The original draft resolution contained the following proposal which were ultimately rejected:

The Assembly therefore calls on member States to:

• 6.1. Sign and/or ratify the relevant Council of Europe conventions on child protection and welfare;

• 6.2. Gather accurate and reliable information about cases of excesses of sects affecting minors, where appropriate in crime and/or other statistics;

• 6.3. Set up or support, if necessary, national or regional information centres on sect-like religious and spiritual movements;

• 6.4. Provide teaching in the history of religions and the main philosophies in schools;

• 6.5. Make sure that compulsory schooling is enforced and ensure strict, prompt and effective monitoring of all private education, including home schooling;

• 6.6. Carry out awareness-raising measures about the scale of the phenomenon of sects and excesses of sects, in particular for judges, ombudsmen’s offices, the police and welfare services;

• 6.7. Adopt or strengthen, if necessary, legislative provisions punishing the abuse of psychological and/or physical weakness and enabling associations to join proceedings as parties claiming damages in criminal cases concerning excesses of sects;

• 6.8. Support, including in financial terms, the action of private bodies which provide support for the victims of excesses of sects and their relatives and, if necessary, encourage the establishment of such bodies.

(Salles 2014)

The entire section above was replaced by:

• 6. “The Assembly therefore calls on the member states to sign and/or ratify the relevant Council of Europe conventions on child protection and welfare if they have not already done so”.

(PACE 2014)

The Assembly also rewrote several articles to align them with international human rights standards and reinforce the protection of freedom of religion of minority religions in the Council of Europe region. As examples:

• 5. The Assembly believes that any religious or quasi-religious organisation should be accountable in the public sphere for any contraventions of the criminal law and welcomes announcements by established religious organisations that reports of child abuse within those organisations should be reported for investigation to the police. The Assembly does not believe that there are any grounds for discriminating between established and other religions, including minority religions and faiths, in the application of these principles.

• 9. The Assembly calls on member States to ensure that no discrimination is allowed on the basis of which movement is considered as a sect or not, that no distinction is made between traditional religions and non-traditional religious movements, new religious movements or ‘sects’ when it comes to the application of civil and criminal law and that each measure which is taken towards non-traditional religious movements, new religious movements or ‘sects’ is aligned with human rights standards as laid down by the European Convention on Human Rights and other relevant instruments protecting the dignity inherent to all human beings and their equal and inalienable rights.

(PACE 2014)

Finally, the international journal, The Economist, in its online edition, summarized it this way:

Yesterday was a big day in the annals of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), a body of legislators which is supposed to act as an important guardian of the continent’s democratic freedoms. (…) [It] saw a victory in PACE for purist advocates of religious liberty, as a long-planned move to curb the activities of “sects” was unexpectedly knocked off course.

(…)

At stake was a resolution which in its original form would have denounced “new religious movements” (to use an alternative, and less loaded description of the groups sometimes described as “sects”) and urged European governments to monitor such bodies and restrict their influence on youngsters. To critics, this seemed like a move to extend the policy of France—which takes a relatively harsh view of small religious groups and has an agency dedicated to countering them— across the whole of Europe. The initiative’s prime mover was a French politician, Rudy Salles, and it found support in some east European countries which have one prevailing religion and regard new players in the field as unwelcome foreign imports.

(…)

It’s not often that Jehovah’s Witnesses, secularists and humanists find themselves on the same side, and rejoicing for the same reason, but this seems to be one such moment.

(Erasmus 2014)

To conclude

If one seeks to understand why the Church of Scientology and Scientologists have been since its inception at the forefront of legal and legislative battles related to freedom of religion or belief, I would propose examining the scriptures of the religion. Amongst many texts that cover the subject of religious freedom, one is the Code of Scientologist, first issued in 1954 and then revised in 1969 and in 1973. In its final version, the code states:

As a Scientologist, I pledge myself to the Code of Scientology for the good of all.

(…)

8. To support true humanitarian endeavours in the fields of human rights.

9. To embrace the policy of equal justice for all.

10. To work for freedom of speech in the world.

11. To actively decry the suppression of knowledge, wisdom, philosophy or data which would help Mankind.

12. To support the freedom of religion.

(…)

15. To stress the freedom to use Scientology as a philosophy in all its applications and variations in the humanities.

(…)

20. To make this world a saner, better place.

(Hubbard 1973)

Furthermore, the Scientology Creed, written in 1954, states:

We of the Church believe:

(…)

That all men have inalienable rights to their own religious practices and their performance.

(Hubbard 1954)

That should be a good basis to understand why freedom of religion and belief is so important to Scientology and why this religion became ‘law changers’ in the field of religion.

Eric Roux

News

Commentaires (0) | Permalien